In the Hollywood movie Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones and his enemies try to capture the lost Ark of the Covenant. At one point in the film, Jones' nemesis pats the Ark and turns to Indiana saying, "You and I are just passing through history. This is history."

That is the feeling one gets in the Old City of Jerusalem. Just walking through the narrow streets and alleys, never mind the shrines holy to three faiths, one is immersed in history.

The Old City covers roughly 220 acres (one square kilometer). The surrounding walls date to the rule of the Ottoman Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-1566). Work began on them in 1537 and was not completed until 1541.

The Old City has a total of 11 gates, but only seven are open (Jaffa, Zion, Dung, Lions’ [St. Stephen's], Herod’s, Damascus [Shechem] and New).

Israel Fact

Jews aren't worried about the Golden Gate being closed. As one tour guide put it, "If the Messiah came this far, he'd find a way in."

David's Tower

One of the closed gates is the Golden Gate, located above ground level and below the Temple Mount. It is only visible from outside the city. According to Jewish tradition, when the Messiah comes, he will enter Jerusalem through this gate. To prevent him from coming, the Muslims sealed the gate during the rule of Suleiman.

You may notice the original gates are angled so that you can't enter directly into the city without making a sharp 90-degree angle turn. This was to prevent enemies on horseback from charging full-speed, straight ahead through them, and to make it difficult to use a long battering ram to break them down. Also, you can see above some of the gates, such as Zion Gate, outside the Armenian and Jewish quarters, a hole through which boiling liquids could be poured on attackers.

The main entrance to the city is the Jaffa Gate, built by Suleiman in 1538. The name in Arabic, Bab el-Halil or Hebron Gate, means "The Beloved," and refers to Abraham, the beloved of God who is buried in Hebron. A road allows cars to enter the city here. It was originally built in 1898 when Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany visited Jerusalem. The ruling Ottoman Turks opened it so the German Emperor would not have to dismount his carriage.

It was announced in August 2014 that the Old City was going to have some work done to make the city more accessable to handicap patrons. This $20 million Shekel ($5.75 million) project will provide handicap accessable ramps, hand rails, and other accommodations so handicap individuals can access areas that they were unable to before. The construction will take place in The Jewish Quarter, at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and the City Of David, all of which had areas that were previously inaccessable to people in wheelchairs and walkers. Other improvements include sign changes for visually impaired individuals, and a new shuttle bus service.

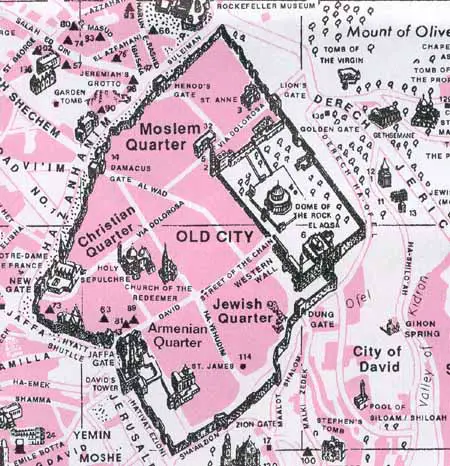

Old City Map

The Old City is divided into four neighborhoods, which are named according to the ethnic affiliation of most of the people who live in them. These quarters form a rectangular grid, but they are not equal in size. The dividing lines are the street that runs from Damascus Gate to the Zion Gate — which divides the city into east and west — and the street leading from the Jaffa Gate to Lion's gate — which bifurcates the city north and south. Entering through the Jaffa Gate and traveling to David Street places the Christian Quarter on the left. On the right, as you continue down David Street, you'll enter the Armenian Quarter. To the left of Jews Street is the Muslim Quarter, and, to the right, is the Jewish Quarter.

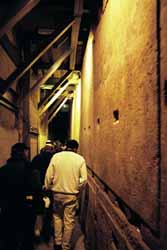

A great way to visit the Old City is simply to wander through the labyrinthine paths and let yourself get lost. For safety reasons, it's best not to travel alone and to be careful about wandering beyond the main thoroughfares of the Muslim Quarter. It is also prudent to explore during the day, though the views of many of the sites -- when you know how to find them -- are often best at night.

Just inside Jaffa Gate, on the left beyond the Tourist Information Office, is a small enclosure with two graves nearly hidden beneath the trees. These are believed to be the graves of the two architects whom Suleiman had rebuild the city walls. They were supposedly murdered either because the Sultan wanted to be sure they could never build anything more impressive for anyone else, or because he was angered by their failure to include Mount Zion within the walls.

The Arab Market

From the Jaffa Gate side of the city, the most striking landmark is the Citadel, which is marked by David's Tower, a misnomer given that the cylindrical structure dates from the 16th century. By contrast, the tall, square tower is 2,000 years old and was built by Herod. Inside the Citadel is a courtyard and museum with exhibits on the history of the Citadel and Old City.

The best way to immerse yourself in the city is simply to head straight down David Street from Jaffa Gate into the Arab market, the souk, where you can expect to be verbally accosted by shopkeepers trying to entice you into their stores and to keep you occupied long enough to buy something. It's a great place to bargain, but keep in mind the shopping tips offered under trip preparation.

As you make your way through the souk, you'll reach different forks. Head to the left to go toward the Christian or Muslim Quarter and the right to reach the Jewish Quarter. The path to the major shrines, the Western Wall, Temple Mount and Church of the Holy Sepulcher, are not very well marked, but anyone you ask should be able to direct you.

If you head toward the Muslim Quarter, or enter the Old City coming from the North from Mea She'arim or somewhere else off Suleiman Street, you'll want to look for Damascus Gate. This is where most Arabs enter the city and you'll find a bustling open-air market filled with people, carts, food and trinkets. Below the gate is a surviving arch built by the Roman Emperor Hadrian in 135 as the main entrance to the city he called Aelia Capitolina.

The Hurva Synagogue

(Top: Old Arch; Bottom: Newly Rebuilt)

The current Jewish Quarter, which today looks almost brand new and usually sparkling clean, dates to roughly 1400. The oldest synagogues — the Elijah the Prophet and Yohanan Ben Zakkai — are roughly 400 years-old. These synagogues are below street level because at the time they were built Jews and Christians were prohibited from building anything higher than the Muslim structures.

In the main plaza, the famous arch that used to stretch skyward where the Hurva Synagogue once stood has now been replaced with a rebuilt and rededicated Synagogue. Originally the Great Synagogue, the Hurva was built in the 16th century, but was destroyed by the Ottomans. The synagogue was rebuilt in the 1850's, but was damaged in the 1948 war and later destroyed after the Jordanians took control of the Old City. After Israel recaptured the Old City in 1967 debate lasted for decades on whether the rebuild the Hurva or leave it in the destroyed state to memorialize the conflict. Finally, in March of 2010 the newly rebuilt Hurva was dedicated and the synagogue is now in regular use.

Nearby is the Ramban Synagogue, named for Rabbi Moshe Ben-Nahman — the Ramban — who helped rejuvenate the Jewish community in Jerusalem in 1267, after it had been wiped out by the Crusaders.

Just off the plaza is the Cardo, which was a Byzantine road, roughly the equivalent of an eight-lane highway, that ran through the heart of the city. Today, a small area is preserved with some of the original Roman columns. Just beyond the columns is an underground mall with a number of Jewish stores and art galleries. This is a good place to purchase Judaica, and it is possible to haggle with shopkeepers. Compare the prices with the shops downtown before you buy.

The Jewish Quarter of today is located on the remains of the upper city from the Herodian period (37 B.C.E-70 C.E.). The Wohl Archaeological Museum contains what are now the underground remains of a residential quarter where wealthy families belonging to the Jerusalem aristocracy and priesthood constructed homes overlooking the Temple Mount. Some archaeologists believe the palace of the Hasmoneans (also known as the Maccabees) is among the ruins.

Israel Fact

Since the 2nd century, refuse has been hauled out of the city through Dung Gate, hence the name.

Two gates lead into the Jewish Quarter. One, just outside the Western Wall plaza, is the Dung Gate. The other is Zion Gate. If you want to bypass most of the tourists, take the path from Yemin Moshe down the hill, across Jaffa Road and up the snake path along the wall to Zion Gate. This was the last gate constructed (in 1540), probably because Mount Zion was inadvertently let outside the city walls. In Arabic it is known as "the Prophet David's Gate" because it faces Mount Zion where David is supposed to be buried. Like other fortress gates, this was built in an L-shape to prevent armies on horseback from charging through the entrance. Today, you only have to worry about cars charging through.

When Rome destroyed the Second Temple in 70 C.E., only one outer wall remained standing. The Romans probably would have destroyed that wall also, but it must have seemed too insignificant to them; it was not even part of the Temple itself, just an outer wall surrounding the Temple Mount. For the Jews, however, this remnant of what was the most sacred building in the Jewish world quickly became the holiest spot in Jewish life. Throughout the centuries, Jews from throughout the world traveled to Palestine, and immediately headed for the Kotel ha-Ma'aravi (the Western Wall) to thank God. The prayers offered at the Kotel were so heartfelt that non-Jews began calling the site the "Wailing Wall."

A large plaza offers access to the Wall. You may take pictures — except on Shabbat — from outside the fenced enclosure near the Wall. The area is open 24-hours and is especially nice to visit when it is quiet late at night or during holidays and bar-mitzvahs when the area is filled with worshippers.

The area near the Wall is divided by a fence — a mechitza — with a small area for women only on one side and a larger area for men on the other. If you don't have a yarmulke, a box at the entrance has paper ones to use while you're near the Wall.

Go right up to the Wall and feel the texture of the stones and take in the awesome size of the structure. The largest stone in the wall is 45 feet long, 15 feet deep, 15 feet high, and weighs more than one million pounds. The Wall is 65 feet (20 meters) high.

Israel Fact

A Jew goes to the Wall every year and puts a prayer in the crack saying: "God please help me win the lottery." Year after year he loses. Finally, after several years, God speaks to him: "Nudnick, will you go and buy a ticket."

Praying at the Wall is a unique experience, one that makes believers feel as close as it is possible to get to the Almighty. You'll notice scraps of paper in the Wall when you are standing up close. These kvitlach, are messages and prayers that people write and put in the Wall, hoping they will be answered.

Entering a tunnel at the prayer plaza, one turns northwards into a medieval complex of subterranean vaulted spaces and a long corridor with rooms on either side. Incorporated into this complex is a Roman and medieval structure of vaults, built of large dressed limestone. The vaulted complex ends at Wilson's Arch, named after the explorer who discovered it in the middle of the 19th century.

|

Along the outer face of the Herodian western wall of the Temple Mount, a long narrow tunnel was dug slowly under the supervision of archeologists. As work progressed under the buildings of the present Old City, the tunnel was systematically reinforced with concrete supports. A stretch of the Western Wall — nearly 1,000 feet (300 meters) long — was revealed in pristine condition, exactly as constructed by Herod. In this confined space, you are walking on the original pavement from the Second Temple period and following in the footsteps of the pilgrims who walked here 2,000 years ago on their way to participate in the rituals on the Temple Mount.

At the end of this man-made tunnel, a 65 foot (20 meters) long section of a paved road and an earlier, rock-cut Hasmonean aqueduct leading to the Temple Mount were uncovered. A short new tunnel leads outside to the Via Dolorosa in the Muslim Quarter.

Ultra-Orthodox Jews oppose organized women's prayer services at the Wall; prayer services they maintain, may only be conducted by males. Public pressure has grown over the years to allow women to pray collectively at the Kotel. Similarly, Jews from the Conservative and Reform movements have been fighting with the Orthodox authorities who control access to the Wall for the right to conduct their own services. Clashes have unfortunately turned violent in recent years; however, the political trend has been moving in the direction of greater pluralism.

Near the Wall, men are often approached by Orthodox Jews who want them to put on tefillin. A few rabbis also hang out in the area and will approach young people and ask them for the time or strike up a conversation. Their intent is to persuade you to go with them to a yeshiva. Going with them can be a rewarding experience -- some people stay for years -- but don't let yourself be intimidated or misled about their purpose.

Ophel Archaeological Garden

Around the corner from the Western Wall, below the southeastern corner of the Temple Mount, is the Ophel Archeological Garden. This excavation reveals 2,500 years of Jerusalem's history in 25 layers of ruins from the structures of successive rulers. The ancient staircase and the Hulda Gate, through which worshippers entered the Second Temple compound, and the remnants of a complex of royal palaces of the 7th century Muslim period are among the antiquities excavated.

A path up from the Western Wall plaza leads to the Temple Mount, or Haram es-Sharif (the Noble Enclosure in Arabic). This 40 acre plateau is dominated by two shrines, the Dome of the Rock (which is not a mosque) and the al-Aqsa mosque. The shrines, built in the seventh century, made definitive the identification of Jerusalem as the "Remote Place" that is mentioned in the Koran.

Israel Fact

The Dome of the Rock is often incorrectly referred to as the "Mosque of Omar" after the Arab caliph Omar Ibn-Khatib who built a mosque nearby. The Dome of the Rock was built 50 years later, in 691, by the Ummayyad caliph, Abd el-Malik.

Muslims remove their shoes and express their devotion to Allah inside the Dome of the Rock, which was built around the rock on which Abraham bound his son Isaac to be sacrificed before God intervened. According to some old maps and traditions, this is the center of the earth. This is also the place where the Koran says Mohammed ascended to heaven. Muslim tradition also holds that the rock tried to follow the Prophet, whose footprints are said to be on the rock. For many years, pilgrims would chip off pieces of the rock to take home with them, but glass partitions now prevent visitors from taking souvenirs. A special wooden cabinet next to the rock holds strands of Mohammed's hair.

Under the rock is a chamber known as the Well of the Souls. This is where it is said that all the souls of the dead congregate.

The al-Aqsa mosque (Ministry of Tourism)

At the southern end of the Temple Mount is the gray-domed al-Aksa mosque. The name means "the distant one," and refers to the fact that it was the most distant sanctuary visited by Mohammed. It is also the place where Mohammed experienced the "night journey," which is why it is considered the third holiest Islamic shrine after Mecca and Medina. In 1951, King Abdullah of Transjordan (Jordanian King Abdullah's great-grandfather) was assassinated in front of the mosque.

Between the mosques is a great water fountain used by Muslims to wash their feet before entering the holy places. Visitors must also remove their shoes. Both mosques are closed to tourists during the five times each day when Muslims pray. The Temple Mount also has a small museum .

A radical group of Orthodox Jews have periodically issued threats against the Muslim shrines in hopes of rebuilding the Temple there. These threats are treated seriously by the Israeli authorities and the group is kept away from the Temple Mount. More mainstream Orthodox opinion forbids Jews from walking on the Temple Mount because of the possibility of unwittingly defiling the place where sacrifices were once offered. Non-Orthodox Jews typically accept the opinion of other authorities who argue the sanctity of the Temple Mount ended when the Temple and altar were destroyed and that it is permissible for Jews to go there so long as they show respect for what was once a holy place.

Despite the name, the Muslim Quarter is also the site of many important Christian sites, including the Church of St. Anne, the Convent of the Sisters of Zion, and the Ecce Homo Church. The Via Dolorosa begins in this section of the city and most of the Way of the Cross is actually in the Muslim rather than the Christian Quarter.

Most Muslims who live inside the Old City have homes in the Muslim Quarter, but this is an area where Jews resided for decades. In recent years, some Jews have moved back to this part of the city, an act viewed by Muslims and many others as unnecessarily provocative, though the Jewish residents would argue they have every right to live anywhere in their capital.

Visitors tour the inside of the Old City of Jerusalem, but most do not know they can climb on top of the ramparts to get a different perspective. Not only do you get a spectacular view of the city beyond the walls, you get a unique look, especially in the Muslim Quarter, at how people live inside the city.

The path along the walls can be accessed from Jaffa, Damascus, Lion's and Zion Gates. The entrances are surprisingly difficult to find, but worth the effort.

The walls are approximately two-and-a-half miles long. It is not possible to circumnavigate the city atop the walls. The street separates the Citadel and Jaffa Gate at one end of the city. At the opposite end, the wall walk ends at St. Stephen's (Lion's Gate), because you cannot walk along the wall surrounding the Temple Mount. This is where the walk beginning at the Jaffa Gate ends. The walk from the Citadel ends short of the Dung Gate, opposite the Jewish Quarter.

From the Citadel, it is possible to look at what once was a moat surrounding Herod's palace. The Citadel was built by the Crusaders in the Middle Ages as a lookout to guard the road to Jaffa. The walk actually ends atop the police station. Beyond the walls, one gets a spectacular view of the new city, Yemin Moshe, the hotels, and shopping mall outside Jaffa Gate.

As one walks around the wall, you can look inside at an Armenian seminary and a huge vacant lot in one of the most ancient parts of the Old City. It is no doubt invaluable as real estate and as an archaeological site. The Armenian authorities, however, will not allow any excavations.

From the top of the wall, you can see the 1948 border where Arabs shot at Jews living in Yemin Moshe, identifiable by its non-functioning windmill, until the border was settled with Jordan. Just to the right is the King David Hotel and behind it the tip of the YMCA tower is just visible. The Sheraton Hotel and the other few “skyscrapers,” also hotels, mark the skyline of what is otherwise a low-level city.

Israel Fact

Lions' Gate has near its crest four figures of lions, two on the left and two on the right. Legend has it that Sultan Suleiman placed the figures there because he believed that if he did not construct a wall around Jerusalem he would be killed by lions. Christians call it St. Stephen's Gate because he is said to have been martyred nearby. The Israeli assault to recapture the Old City in 1967 was made through this gate.

It is also possible to see the cemetery of Dormition Abbey just beyond the SE corner of the walls. This particular route is separated from the Jewish Quarter by a road inside the wall so that it is not possible to see much. Beyond the walls, however, it is possible to get a panoramic view of what the rest of the world calls the occupied territory. Closer to the Old City, it is possible to see the Arab village of Silwan and, if someone points it out, the City of David excavations. Toward the exit it is possible to see large depressions that are the ruins of cisterns from the 4th and 5th century Byzantine period.

The path along the ramparts in the Muslim Quarter is even more interesting. Making your way toward the Temple Mount from Damascus Gate, it is possible to look inside the courtyards of Muslim homes. Outside, across Suleiman Street, you can see the Rockefeller Museum, which houses antiquities found from archaeological excavations and other exhibits. When you reach the far corner of the City, you can get a wonderful view of Mount Scopus, the Hebrew University, Mount of Olives and various churches.

The best way to follow the Via Dolorosa, or way of suffering, is to enter Lion's Gate (St. Stephen's Gate) from the eastern side of the City (beside the Temple Mount). This is the route Christians believe Jesus traveled carrying the cross from his trial to the place of his crucifixion and burial. The 14 stations commemorate incidents along the way. The first seven stations wind through the Muslim Quarter. The last five are inside the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The tradition of following the Via Dolorosa dates to the Byzantine period.

Station I -- The place where Pontius Pilate's judgment hall once stood and Jesus was condemned to death.

Station II -- The Monastery of the Flagellation where Jesus was given the cross.

Station III -- The spot where Jesus fell under the weight of the cross for the first time.

Station IV -- Where Mary came out of the crowd to see her son.

Station V -- Simon the Cyrene was taken out of the crowd by the Romans to help Jesus carry the cross.

Station VI -- Recalls the tradition of Veronica stepping up to Jesus and wiping his face.

Station VII -- Where Jesus fell for the second time.

Station VIII -- The place where Jesus consoled the women of Jerusalem.

Station IX -- Where Jesus fell for the third time.

Station X -- Jesus is stripped of his garments.

Station XI -- Jesus is nailed to the cross.

Station XII -- The place where Jesus died on the cross.

|

Station XIII -- The spot where Jesus' body was taken down.

Station XIV -- The tomb of Jesus.

The Church of the Holy Sepulcher is revered by Christians as the site of the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. In the 4th century, Helena, the mother of Emperor Constantine and a convert to Christianity, traveled to Palestine and identified the location of the crucifixion; her son then built a magnificent church. The church was destroyed and rebuilt several times over the centuries. The building standing today dates from the 12th century.

Control of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher is zealously guarded by different denominations. The Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholics, Armenians and Copts are among those that oversee different parts of the Church. In the 12th century, fighting among different denominations over who should keep the key to the church led the Arab conqueror Saladin to entrust the key to the Muslim Nuseibeh and Joudeh families.

Today, eight centuries later, the 10-inch metal key is still safeguarded in the house of the Joudeh family. Every morning at dawn, Wajeeh Nuseibeh, who took over the job of doorkeeper from his father 20 years ago, picks up the key and opens the massive wooden church doors. Every night at 8:00 p.m. he returns to shut and lock them.

For years, Israel tried to convince the Christian denominations to open a second exit to the Church for safety reasons. In 1840, a devastating fire caused a panic that led to many deaths, and Israeli officials became especially concerned about the danger with the expected crush of tourists arriving for the year 2000 celebrations. Agreement was finally reached in June 1999 to open another exit, but this has provoked a new dispute over who will have the key to the new door.

The Old City is said to be divided into quarters because of the concentration of Jews, Christians, Muslims and Armenians in corners of the nearly square area enclosed by the Turkish walls. The Armenian section is actually the smallest, comprising about one-sixth of the area of the Old City. If you enter the city from Jaffa Gate and turn left, walk past the Citadel and police station and continue down the narrow street – watch out for cars! – you'll run smack into the Armenian Quarter. From Zion Gate, the first thing you will see are the Armenian shops where you can find beautiful hand-made ceramics.

Israel Fact

The Armenian-style ceramics in the Arab market are usually mass produced. You get the real thing in the Armenian Quarter and can even watch the artisans create their masterpieces.

The Armenians claim a presence in Jerusalem since the first century when an Armenian battalion fought under the Roman emperor Titus. The Armenians adopted Christianity as their official religion in 286 C.E., even before the Romans and, for the last 1,700 years, have been ensconced in Jerusalem, frequently finding themselves between warring factions. The Armenian Quarter was established in the 14th century. Today, approximately 2,500 Armenians live in Jerusalem and another 1,500 elsewhere in Israel.

The Armenians are not Palestinians, but they generally sympathize with their political agenda, although the Armenians have not supported the idea of Palestinian control over the Old City. In fact, during the Camp David Summit, leaders of the Armenian church insisted the Christian and Armenian Quarters were inseparable and expressed their preference for international guarantees.

The Armenian section is almost a city within the city. The walled compound surrounds the Church of St. James, the Convent of the Olive Tree, the Armenian Patriarch residency, a monastery and a number of shops.

St. James Church, built in the mid-12th century, is named for the brother of Jesus, who was the first bishop of the Jerusalem church and for James the Apostle. It is renowned for its beauty. The domed ceiling is illuminated by gold and silver lamps. Jesus' brother James is said to be buried in the central nave and beyond the wooden doors inlaid with mother-of-peal and tortoise shell is a shrine where the head of St. James is buried.

The St. James Monastery, which takes up about two-thirds of the quarter, houses gifts left by pilgrims over the last 1,000 years. It also includes a quiet residential area. The Gulbenkian Library is also inside the monastery. It holds more than 100,000 volumes, many dating back hundreds of years. The Mardigian Museum is nearby and it contains exhibits on Armenian art and culture and the genocide of 1915.

Oddly enough, only one Armenian church is in the Quarter, but four other denominations (Syrian, Maronite Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and Anglican) have churches in this part of the city.