From learning activities to transitions, children’s challenging behavior can influence every aspect of a classroom. This disruption often can overwhelm early childhood teachers, who report feeling concerned and frustrated about classroom management (Hemmeter, Ostrosky, & Corso 2012) as well as underprepared to address challenging behavior proactively (Stormont, Lewis, & Covington Smith 2005). These concerns are justified for several reasons. Children who frequently exhibit challenging behavior may have fewer friends or lower academic performance, and research links the persistent challenging behavior of young children to more serious behavior problems and negative consequences as they get older (Dunlap et al. 2006; McCartney et al. 2010). Young children who demonstrate difficult behavior are more likely to face persistent peer rejection and negative family interactions (Patterson & Fleischman 1979; Crick et al. 2006) and to be disciplined by school professionals (Strain et al. 1983). As high school students, these children are more likely to experience school failure and drop out (Kazdin 1993; Tremblay 2000) as well as encounter the juvenile justice system (Reid 1993; Dishion & Patterson 2006). But just as behavior can affect all aspects of a learning environment, all the aspects of a learning environment can be structured to promote positive behavior.

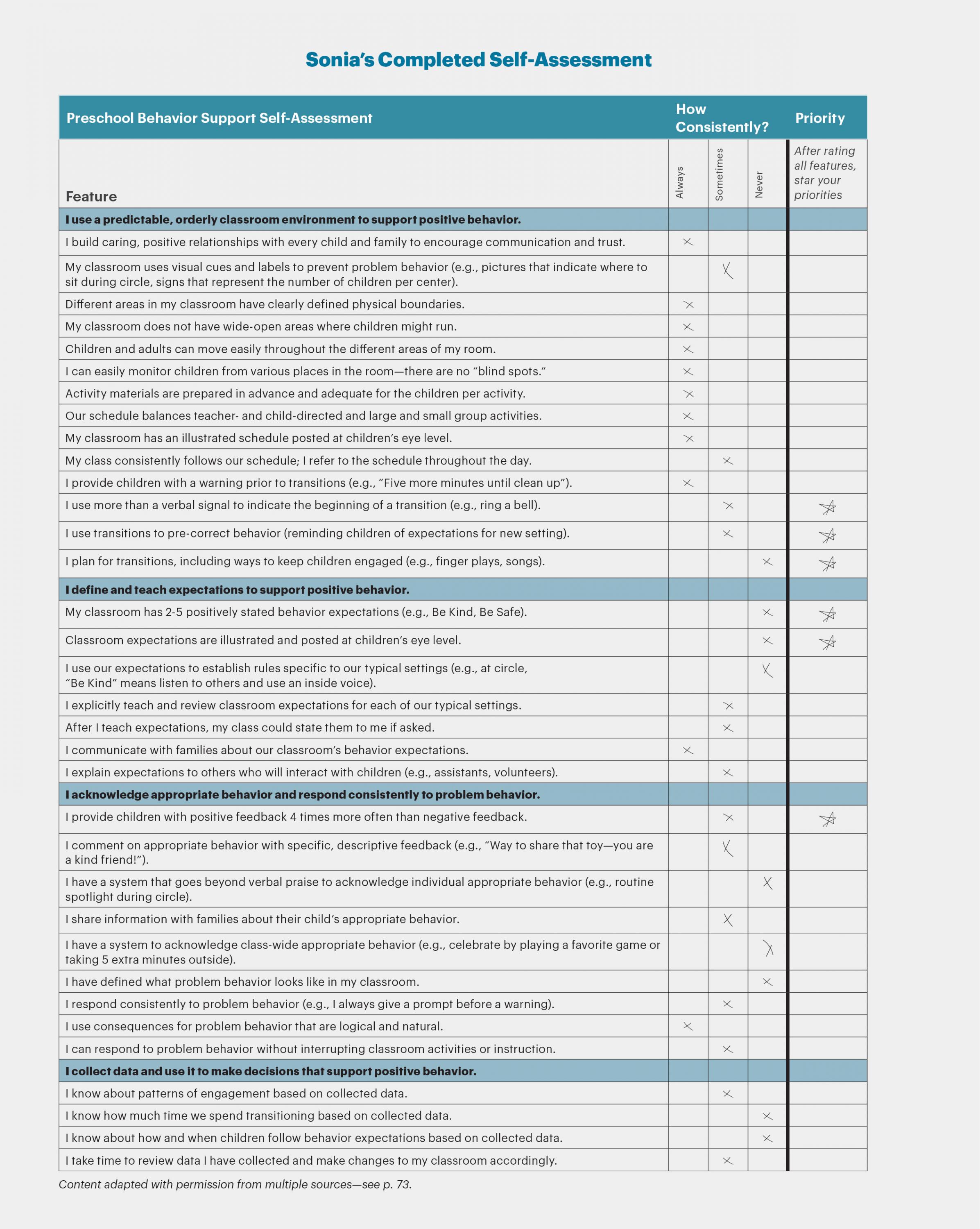

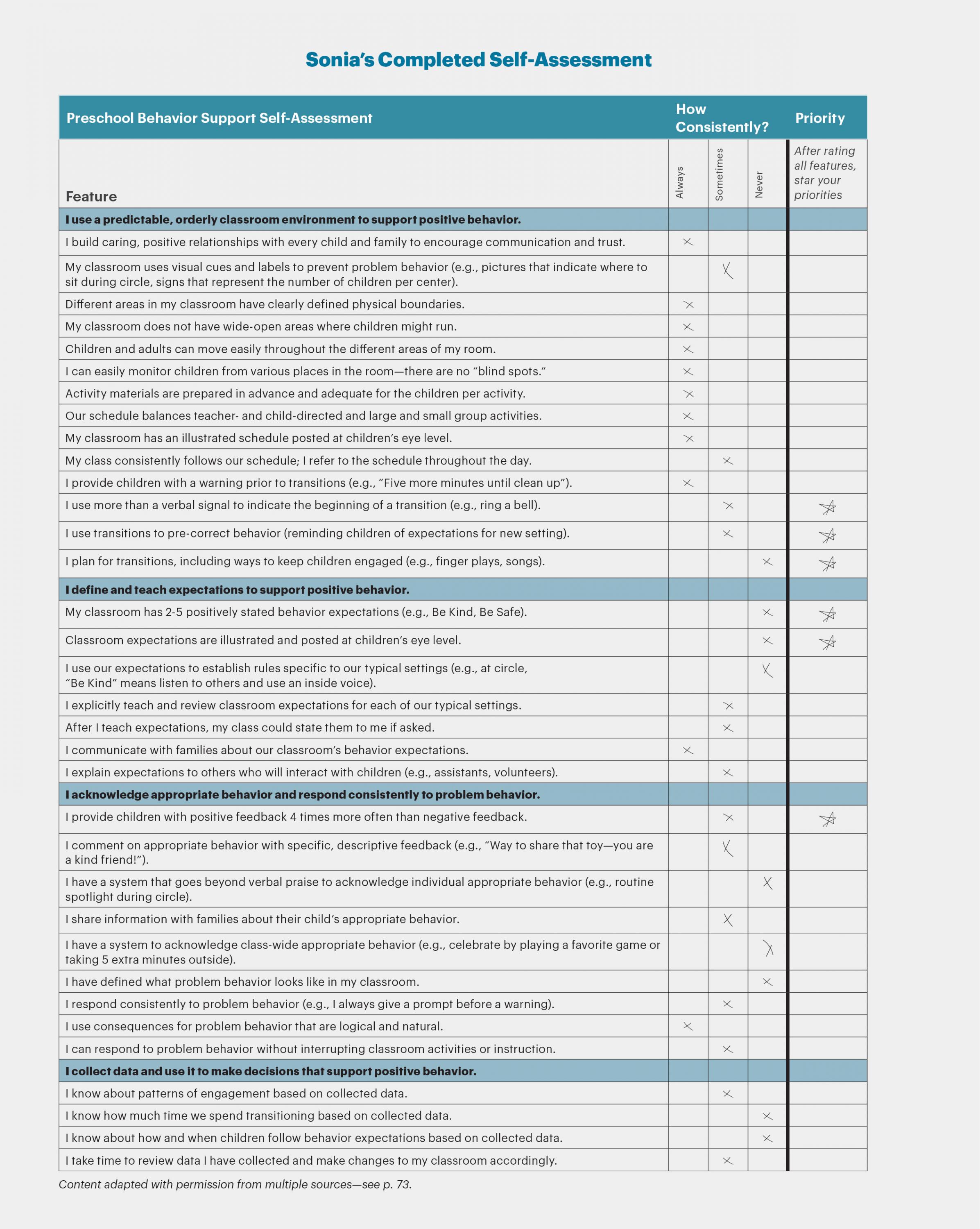

This article shares a teacher self-assessment tool—the Preschool Behavior Support Self-Assessment—that helps teachers of preschool children examine how their classrooms support children’s positive behavior. The self-assessment aligns with the key features of positive behavior support (PBS), an approach grounded in theory (see Singer & Wang 2009 for a review), supported by research (see Dunlap et al. 2006 for an extensive review and synthesis of PBS in early childhood), and applicable to the values and needs of early childhood settings. PBS is a comprehensive process often applied as a continuum of increasingly individualized practices (Stormont et al. 2008; Fox et al. 2010; Horner, Sugai, & Anderson 2010). This continuum involves universal supports for all children that include building strong relationships and providing a high-quality environment, more targeted preventive practices for some children who may need more social-emotional support, and individualized interventions for children who need extensive support. The elements in the self-assessment address universal practices appropriate for all children during day-to-day classroom activities, so this tool is appropriate for all preschool settings, whether or not they have formally adopted PBS.

Designed to be brief, the self-assessment can be completed by teachers in 10 to 20 minutes. The tool contains four sections aligned with preventive practices in positive behavior support:

Combined, these features provide a fairly comprehensive picture of practices that teachers can use to address the behavior of all preschool children, not just those who tend to use challenging behavior.

The self-assessment was developed by the authors and adapted from the three assessment tools used for assessing the implementation of PBS practices: the Teaching Pyramid Observation Tool (TPOT) for Preschool Classrooms (Hemmeter, Fox, & Snyder 2014); the Preschool-Wide Evaluation Tool (PreSET) (Steed, Pomerleau, & Horner 2012); and the Positive Behavior Support Classroom Management: Self-Assessment Revised (Simonsen et al. 2006). General categories and items were modeled after the Positive Behavior Support Classroom Management: Self-Assessment Revised, a self-assessment tool designed for K–12 teachers. Language and key features specific to preschool settings were modeled on the TPOT and PreSET, both of which are designed for early childhood settings but are research tools used by outside observers.

Like all tools, self-assessments have limitations. When teachers assess themselves, they may not see their practices in the same way outside observers do. Similarly, teachers’ perceptions about how they communicate with families, children, or colleagues may be very different from the way those individuals see the interactions. However, when used thoughtfully and carefully, this self-assessment can be a powerful tool for reflection. As one early childhood teacher who used this tool commented, “Self-assessments are only helpful if you find the time and see the purpose of using them. This form did both for me.”

The classroom environment plays a central role in encouraging positive behavior. Thus, the first section of the self-assessment contains items that relate to creating a predictable, orderly learning environment. Items in this section focus on developing positive relationships with children and families, designing the physical environment of the classroom to maximize structure and predictability, developing clear and consistent schedules and routines, and implementing effective transitions.

Warm, responsive relationships build a foundation for positive behavior (Hemmeter, Ostrosky, & Corso 2012). Consistent and predictable classroom environments, schedules, and routines can increase children’s independence, ability to anticipate change, and likelihood of using appropriate behavior. Transitions can be a particular concern related to young children’s behavior and frequently impact how orderly the classroom environment is. Teachers can support positive behavior throughout transitions by planning for them ahead of time, alerting children before transitions occur, and providing a clear signal at the beginning of each transition. For example, when transitioning from free play to cleanup, rather than glancing at the clock and announcing “We have to clean up now,” a teacher might plan with assistants where they will be positioned in the classroom during cleanup. Providing a warning and building in reminders of expectations can also be helpful, such as a teacher giving the reminder: “We have five minutes left to play. Can we start any new projects now?” (Children: “No!”) When five minutes have elapsed, the teacher gives a clear audio and visual cue that the transition is beginning by playing a chime and switching off the lights or starting a song that incorporates hand motions. Teachers can also treat transitions as opportunities to discuss expectations for the next activity (e.g., commenting while cleaning up, “We’re cleaning up now, and then we’ll all sit together on the rug to read”).

The second section of the self-assessment addresses expectations. Taking an instructional approach to behavior gives children the chance to learn and practice how to behave in a learning environment. Adults often assume that children know how to act appropriately (Stormont et al. 2008). Teachers can avoid this pitfall by identifying a small number of behavioral expectations (e.g., be kind, be safe), defining specific examples (rules) of what those expectations look like across common settings or routines (e.g., circle time, centers, snack, bathroom, playground), and directly teaching children how to put those expectations into practice. For example, a teacher who has the classroom expectation “Be safe” may have decided that one component of this is that children must use “walking feet” when inside and on paved areas outside, but they may run on the grassy area of the playground. Teaching this specific example of what it means to be safe could involve a game outside in which the teacher holds up a picture of “running” or “walking” as children respond by moving to the appropriate areas of the playground. In the classroom, teaching this expectation could involve making a picture chart of places where children may run or walk during a group meeting.

The third area of the self-assessment involves practices that teachers use to acknowledge appropriate behavior and respond to challenging behavior. While teachers often comment on children’s learning or academic behavior, they rarely give feedback about appropriate social behavior (Stormont et al. 2008). Providing children with specific, positive feedback helps them learn what appropriate behavior looks like. Verbally commending appropriate behavior as it occurs is an essential tool for classroom management, but teachers can create opportunities for more formal recognition of positive behavior. Teachers could, for example, send home a certificate when they “catch” children demonstrating positive social behavior.

It is important that teachers also take care to define for the classroom community what inappropriate behavior looks like and develop a plan to respond to it consistently and logically. For example, some behavior (e.g., biting and hitting) may require immediate intervention to ensure children’s safety, while others (e.g., not participating during cleanup) may first lead to a prompt to use the appropriate behavior (“What are you going to clean up, blocks or puzzles?”) and then a reminder (“We are cleaning up now to take care of our classroom. Let’s work together on putting away these blocks.”) if the prompt is ignored.

Early childhood teachers can take simple steps to collect data in their own classroom and learn valuable information about behavior in their class (Krasch & Carter 2009). Using simple forms like tally sheets or checklists, teachers can document which times of the day children tend not to follow expectations, whether children are engaged or off task during free play, and how long transitions between activities take (Krasch & Carter 2009). Teachers can then use the data to make decisions that support positive behavior more effectively. For example, teachers can collect data to learn which expectations children find difficult to meet and to identify when and where challenging behavior is likely to occur (Krasch & Carter 2009). They can use this information to target an issue by revisiting an expectation, providing more practice, or making changes to a routine that is not working. Data may also reveal information about children’s engagement, time spent in transitions, or individuals who need additional support to meet behavioral expectations.

To use the tool, teachers first rate how consistently (Always, Sometimes, Never) they implement each feature listed. Consistency in schedules, expectations, and consequences help children gain independence and learn that appropriate behavior works. Next, teachers review the features they rated Always to identify their strengths. Teachers then review features they rated Sometimes or Never and determine which of them are priorities for improvement. Finally, teachers create an action plan that outlines measurable steps they will take to achieve classroom management goals. The following vignette illustrates how a teacher might use the tool.

Sonia has taught preschool in a community-based center for five years. Her favorite part of teaching is connecting with her class; she learns a lot about the children and creates in-depth projects that relate to their interests. Six weeks into the school year, Sonia feels comfortable with her class of a dozen 4-year-olds. She has a sense of each child’s strengths, and she has worked with parents to set goals for their child. Sonia would like to begin the class’s first project, but she wonders if everyone is ready.

The class spends a lot of time moving from activity to activity, and problems such as pushing tend to prolong transition times. Sonia is frustrated by the need to remind children about classroom expectations several times each day. Sonia believes her class has the skills to follow the rules and routines, but she feels that the children are not as orderly as they might be. To investigate how she supports behavior, Sonia decides to take the Preschool Behavior Support Self-Assessment.

Sonia began by evaluating how consistently she implemented each behavior support feature across the four areas on the survey. (See “Sonia’s Completed Self-Assessment.”)

After rating all the behavior support features, Sonia reviewed the items she marked Always. She listed summaries of several things she was already doing to support positive behavior: (1) “My strong relationships with children and families support engagement”; (2) “My classroom centers are well organized, nicely defined, and the right size”; and (3) “My class schedule is balanced, posted, and illustrated with photos.”

Sonia had always taken pride in the relationships she built with children and their families but had never considered how they might affect behavior. Having strong relationships creates a foundation for social and emotional development and “provides a safe context for tackling difficult issues related to challenging behaviors, should they arise” (Hemmeter, Ostrosky, & Corso 2012, 35). That is, when teachers have strong positive relationships with children, they can be more effective in helping them to develop positive social behavior. Similarly, when teachers have strong positive relationships with families, they can be more effective in communicating concerns about a child’s behavior and working collaboratively with families to address these concerns.

Sonia reviewed the items she rated Sometimes or Never and starred the items that represented major concerns. She noticed that several items relating to transitions had Sometimes or Never answers, so she made working on those a priority. She planned to create and post behavior expectations, since several other items on the self-assessment (“Classroom expectations are illustrated and posted at students’ eye level,” “I use our expectations to establish rules specific to our typical settings”) stem from using these expectations. Sonia also felt it was important to provide more positive feedback in the classroom. However, since most of her priorities related to transitions, Sonia decided to focus on that area first.

Once Sonia identified her top priority—smoother transitions—she created a plan to move from reflection to action (see “Sonia’s Action Plan”). This step provides a method to help think through the changes needed to move from current implementation to the goal. Sonia decided that she needed to be more consistent in signaling upcoming transitions and making adjustments—precorrecting—during them.

Sonia first set a specific goal to address this need (“Build systems to increase consistency during transitions”) and then outlined steps she could take to achieve this goal (create a “transition helper” job; add transitions to the lesson plan; and make cue cards for transition expectations, such as staying in your “bubble” in line, using whisper voices in the hallway, and staying with the group). In some cases, steps might include gathering information or talking to colleagues (e.g., brainstorming transition activities with a mentor teacher), as well as making changes in the classroom. By keeping her steps clear and observable, Sonia created a plan she could follow.

Sonia also included how she would monitor her progress. This step helps a teacher think through her plan so that she can easily track what she has accomplished. After finishing the plan, Sonia set a date to complete the self-assessment again so she could see her progress and possibly identify new areas to address.

| Sonia's Action Plan | |

| GOAL: Build systems to increase consistency during transitions | Monitoring |

| Steps/Process |

1. Create new “transition helper” job (set timer when five-minute warning given and turn off lights when timer rings)

2. Add Transitions section to lesson plan form

3. Create transition cue cards that list expectations for next activity (to encourage precorrections)

4. Later: Collect data on transitions (How often do I precorrect? Am I following my lesson plans? How long are transitions?)

Plan a date for your next self-assessment: 5/25/16

1. Job added to job chart

3. Cue cards finished

Many teachers may find it helpful to use the tool as a self-check six weeks or so into the school year. Self-assessment at this time helps teachers reflect on what they have already established in the classroom, and it leaves a significant amount of time to make changes. Teachers can then self-assess at the midpoint or year-end and measure their progress. Positive change can serve as a personal motivator and demonstrate professional growth.

Teachers can use this flexible tool several ways. For example, they can collaborate with an assistant or peer. Partners can exchange feedback, provide support, and hold each other accountable throughout the process. Most of the features addressed in the self-assessment could be applied in settings other than classrooms, so any colleague who interacts with children could be a partner—bus drivers, cafeteria workers, or the school librarian.

Regardless of the way a teacher decides to approach the self-assessment, it is important to remember that change is gradual. An action plan that uses observable, measurable steps can help teachers focus on achievable outcomes rather than the number of things that could be done. When teachers complete one self-assessment, they can plan a date for their next to create a cycle of reflection and positive action. Along the way, teachers working toward change should take time to review their progress, celebrate their success, and remember not to get overwhelmed. (See “The Self-Assessment in Action—Teacher Feedback” to learn about four teachers’ experiences with the tool.)

As a tool for teachers, this self-assessment outlines key features of classroom-wide positive behavior support and provides a framework for reflection and action. The self-assessment may lead to beneficial outcomes for children and teachers. When teachers work intentionally to build positive classroom environments, they also build strong foundations for social-emotional and academic success.

“I learned that I do not collect data on the children’s behavior and engagement with the same thoroughness that I collect data on cognitive, social and emotional, and academic skills.”

Four teachers who completed this self-assessment provided feedback within six weeks of beginning their first action plan. They shared the changes that they made in their practices and in the classrooms, and the results of the changes. These teachers have had a variety of experiences with positive behavior support (PBS). Three teach in a setting with program-wide PBS at the Pearl Buck Preschool in Eugene, Oregon; one teacher works in a public school in Washington, DC, that did not use program-wide PBS.

The teachers who used the tool expressed their appreciation for reflection and said that it helped them direct that process. For example, one teacher said, “I am always looking to improve my practice. My hopes were that by assessing myself, I would come up with a better understanding of how to utilize my strengths and work on areas that needed improvement.”

All four reported that they made concrete changes as part of their action plans. They made a variety of adjustments, but most focused on increasing the consistency of different daily practices. The practices included providing positive feedback, teaching expectations for transitions, and giving warnings before cleanup. They learned from the process, and the changes had an impact on the classroom environment. A teacher who chose to work on her ratio of positive to negative feedback said, “Since the number of negative pieces of feedback has mostly disappeared, there is some tension relieved—especially for the children who more often receive negative feedback.”

Self-assessment also led the teachers to consider the role of data in documenting behavior. One teacher said, “I realized that while I see PBS in the classroom and see how much of my teaching style naturally aligns with it, I have very little data to support the growth and changes in the children as a result of the way PBS has impacted them.” Another teacher shared these thoughts: “I learned that I do not collect data on the children’s behavior and engagement with the same thoroughness that I collect data on cognitive, social and emotional, and academic skills.” Both of these teachers said they would need more time and support to develop systems for data collection. However, with such a system, one teacher explained, “I expect more fundamental changes to take place.”

The authors’ self-assessment form includes content adapted, with permission, from the following sources: Hemmeter, M.L., L.K. Fox, & P. Snyder. 2014. Teaching Pyramid Observation Tool (TPOT™) for Preschool Classrooms, Research Edition. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc. • Simonsen, B., S. Fairbanks, A. Briesch, & G. Sugai. 2006. Positive Behavior Support Classroom Management Self-Assessment Revised (7r). Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut • Steed, E.A., T.M. Pomerleau, & R.H. Horner. 2012. Preschool-Wide Evaluation Tool (PreSET™), Research Edition. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc.

Crick, N.R., J.M. Ostrov, J.E. Burr, C. Cullerton-Sen, E. Jansen-Yeh, & P. Ralston. 2006. “A Longitudinal Study of Relational and Physical Aggression in Preschool.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 27 (3): 254–68.

Dishion, T.J., & G.R. Patterson. 2006. “The Development and Ecology of Antisocial Behavior in Children and Adolescents.” Chap. 13 in Developmental Psychopathology, 2nd ed., vol. 3, Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation, eds. D. Ciccetti & D.J. Cohen, 503–41. New York: Wiley.

Dunlap, G., P.S. Strain, L. Fox, J.J. Carta, M. Conroy, B.J. Smith, L. Kern, M.L. Hemmeter, M.A. Timm, A. McCart, W. Sailor, U. Markey, D.J. Markey, S. Lardieri, & C. Sowell. 2006. “Prevention and Intervention With Young Children’s Challenging Behavior: Perspectives Regarding Current Knowledge.” Behavioral Disorders 32 (1): 29–45.

Fox, L., J.J. Carta, P.S. Strain, G. Dunlap, & M.L. Hemmeter. 2010. “Response to Intervention and the Pyramid Model.” Infants and Young Children 23 (1): 3–13.

Hemmeter, M.L., L. Fox, & P. Snyder. 2014. The Teaching Pyramid Observation Tool (TPOT) for Preschool Classrooms, Research Edition. Baltimore: Brookes.

Hemmeter, M.L., M.M. Ostrosky, & R.M. Corso. 2012. “Preventing and Addressing Challenging Behavior: Common Questions and Practical Strategies.” Young Exceptional Children 15 (2): 32–46.

Horner, R.H., G. Sugai, & C.M. Anderson. 2010. “Examining the Evidence Base for School-Wide Positive Behavior Support.” Focus on Exceptional Children 42 (8): 1–14.

Kazdin, A.E. 1993. “Adolescent Mental Health: Prevention and Treatment Programs.” American Psychologist 48 (2): 127–41.

Krasch, D., & D.R. Carter. 2009. “Monitoring Classroom Behavior in Early Childhood: Using Group Observation Data to Make Decisions.” Early Childhood Education Journal 36 (6): 475–82.

McCartney, K., M. Burchinal, A. Clarke-Stewart, K.L. Bub, M.T. Owen, J. Belsky, & NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. 2010. “Testing a Series of Causal Propositions Relating Time in Child Care to Children’s Externalizing Behavior.” Developmental Psychology 46 (1): 1–17.

Patterson, G.R., & M.J. Fleischman. 1979. “Maintenance of Treatment Effects: Some Considerations Concerning Family Systems and Follow-Up Data.” Behavior Therapy 10 (2): 168–85.

Reid, J.B. 1993. “Prevention of Conduct Disorder Before and After School Entry: Relating Interventions to Developmental Findings.” Development and Psychopathology 5 (1–2): 243–62.

Simonsen, B., S. Fairbanks, A. Briesch, & G. Sugai. 2006. Positive Behavior Support Classroom Management: Self-Assessment Revised (7r). Storrs: University of Connecticut.

Singer, G.H.S., & M. Wang. 2009. “The Intellectual Roots of Positive Behavior Support and Their Implications for Its Development.” In Handbook of Positive Behavior Support, eds. W. Sailor, G. Dunlap, G. Sugai, & R. Horner, 17–46. New York: Springer.

Steed, E.A., T.M. Pomerleau, & R.H. Horner. 2012. Preschool-Wide Evaluation Tool (PreSET) Research Edition: An Assessment of Universal Program-Wide Positive Behavior Support in Early Childhood. CD-ROM ed. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Stormont, M., T.J. Lewis, R. Beckner, & N.W. Johnson. 2008. Implementing Positive Behavior Support Systems in Early Childhood and Elementary Settings. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Stormont, M., T.J. Lewis, & S. Covington Smith. 2005. “Behavior Support Strategies in Early Childhood Settings: Teachers’ Importance and Feasibility Ratings.” Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions 7 (3): 131–39.

Strain, P.S., D.L. Lambert, M.M. Kerr, V. Stagg, & D.A. Lenkner. 1983. “Naturalistic Assessment of Children’s Compliance to Teachers’ Requests and Consequences for Compliance.” Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 16 (2): 243–49.

Tremblay, R.E. 2000. “The Development of Aggressive Behaviour During Childhood: What Have We Learned in the Past Century?” International Journal of Behavioral Development 24 (2): 129–41.